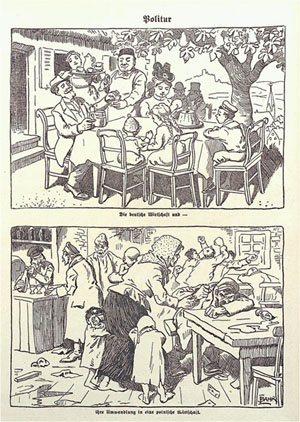

1. „the German Economy and ist transformation into a Polish economy“ – German Stereotypes of Poles seen through a cartoon

Questions

Description and Analysis

The first part of the cartoon shows a German family in the garden of a restaurant. In the background we see a small town with a steeple and a low mountain with a castle. Under a tree at a table, a couple and its four children are sitting, the oldest in a sailor suit, the youngest held by its mother. The wife looks demurely to the side while the husband, a beer mug in front of him and a cigar in his hand, pays the owner of the tavern. At the same time his wife or employee brings the ordered coffee to the table. The oldest sister takes good care of the second-youngest child; in the background are two other guests. The whole atmosphere is relaxed and friendly; one dines beneath a tree, obviously there is “Kaiser weather”.

The second part of the cartoon is antithetical to the first. We look into the interior of a tavern. In the center of the picture is a gram bent woman, two desperate children are pulling at her skirt, a third one she holds in her arms. She is trying to get her completely drunk husband from the pub. The husband sits on a table, arm and head resting on it, his fists clenched as a sign of protest against his wife. The glass of wine he has knocked in his drunken stupor. Behind him, at another table there is a fight between different men, the fists are raised; while at the same time another person sleeps – head and arms on the table. On the left side of the cartoon one sees something like a counter, cobbled together with plain wood. Two men stand in front of it, behind it a disgruntled landlord serves wine. The whole scene and atmosphere is marked by drunkenness and violence, resentment and dirt. The walls of the tavern are not plastered, everything is a mess, glasses and other objects are lying on the floor, tables and floor are littered with wine or water.

Geographical/Historical Context

Obviously the cartoonist shows a stereotype of the „Polish economy“: It is just the same what the Polish do, it won’t be successful and ends in chaos. Despite this the image of Poland wasn’t entirely negative. Since the 18th century the Polish ‘national character’ has been assessed positively and negatively at the same time. For one example the Poles can be characterized as a freedom-loving people, whereas the Poles can be characterized as fanatical at the same time. Even though these meanings are different they are based on a similar trait. Depending on the context and on the political situation this trait can be described positively or negatively. According to Jaworski this explains the fast switching between ‘Poland-scolding’ and ‘Poland-love’.

The stereotyp of the “polish economy” is a thoroughly known one and common since the 18th century. After the partitions of Poland in the 18th century, the structure of the old Polish kingdom was vilified as chaotic, ineffective and weak; thus the partition was justified. In addition to the notion of the disorderly state came the idea of a dilapidated and rotten Polish aristocratic world; this image of Poland was opposed by the image of a hard-working, disciplined and clean Prussia. The for three centuries well known stereotype had a dual role: the ‘stereotype of the other’ and the ‘stereotype of the self’. The presumably German virtues were the more advantageous the less shining the Polish character traits were.

The negative image of the backwardness of Poland became turned positive in the Romantic period and Poland was seen as a region of exotic authenticity. The divisions, but mainly the November Uprising of the 1830s – when the Poles rose against the Russian rule – caused the so called ‘great Emigration’. After the suppression of the Uprising over 9000 Poles – mainly soldiers, officers and intellectuals fled to Western Europe. Across Europe the Poles were hailed as “Sturmvögel” of the revolution.

Presentation

The cartoon has been published in Kladderadatsch (7.27.1919). Kladderadatsch was a political-satirical weekly, published between 1848-1944.